Obfuscation Isn’t a Fix, And It Cost Them $2,500 — A Real-World Case Study

Obfuscation Isn’t a Fix, And It Cost Them $2,500 — A Real-World Case StudyChallenge AcceptedA while ago, I performed a penetration test on a major web application owned by one of my clients. During the assessment, I identified several critical vulnerabilities. Although these flaws weren’t easy to find — they required in-depth analysis and carefully crafted requests — they posed a serious risk to the platform’s integrity and user data.Given the severity of the findings, I expected the development and management teams to prioritize proper remediation. But instead, they chose a different path.Rather than fixing the underlying security issues, they decided to encrypt the entire body of each HTTP request— for example, encrypting login credentials or parameter values — in an attempt to prevent attackers from understanding or reproducing the vulnerabilities.Their idea was to “hide” the vulnerabilities behind encrypted traffic, giving them six months to work on actual fixes. In theory, this would slow down any attacker trying to identify or exploit the issues.I explained why this approach wouldn’t hold. Obscuring insecure functionality doesn’t make it secure — it just shifts the problem and adds complexity without eliminating the risk. I even challenged them: if I could still exploit the vulnerabilities despite the encrypted requests, they would pay me an additional $2,500.Spoiler: they did.Let’s walk through the scenario, why encryption is not a substitute for proper remediation, and what this taught both sides about the real cost of avoiding fixes.The first request is a POST request, in which data is sent encrypted within the HashData parameter. However, after decryption, the data appears to be unreadable.Encrypted RequestEncrypted ResponseUpon inspecting the JavaScript bundle (main.xxxxxxx.chunk.js), I identified a function named HashData, which was responsible for encrypting request data. This function was used in two key places, but only one of them leveraged a request interceptor pattern, which allowed injection or modification of outgoing payloads before being sent.HashData Function Used In First PlaceHashData Function Used In Second PlaceIn this case (Second Place), the developer has used an interceptor method for the request in order to apply modifications. We use a breakpoint to sniff and analyze it.Analyze HashData FunctionDespite the code being minified, I was able to use online tools to beautify it and analyze the logic.HashData FunctionThe encryption process involved the following:A random 256-bit key was generated for each request using a function like random().The request body was encrypted using AES, with this random key as the encryption key.The random key itself was then encrypted using a static RSA public key and attached to the request.The encrypted data was finally Base64-encoded and stored or transmitted (sometimes via localStorage or directly in the request).The AES encryption function is defined as follows:function s(e, t) {var n = t.toString();return r.a.AES.encrypt(JSON.stringify(e), n).toString()}e is the input data that gets converted to JSON and then encrypted.t is the encryption key.The function returns the encrypted result as a string (i.e., the server response).Here’s a simplified version of the AES encryption logic:function encrypt(data, key) { return CryptoJS.AES.encrypt(JSON.stringify(data), key.toString()).toString();}The AES decryption function is defined as:function u(e, t) { if (void 0 !== e) { var n = r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(), t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8); return JSON.parse(JSON.parse(n).data) }}e is the encrypted data.t is the encryption key.The decrypted result is parsed from JSON and returned as the original data.Here’s a simplified version of the AES decryption logic:function decrypt(encryptedData, key) { const decrypted = CryptoJS.AES.decrypt(encryptedData.toString(), key).toString(CryptoJS.enc.Utf8); return JSON.parse(JSON.parse(decrypted).data);}This means that the payload encryption relied entirely on a client-generated key — which I could capture at runtime using browser breakpoints — and a public RSA key for wrapping that AES key.On the server side, the process was reversed:The encrypted AES key was decrypted using the server’s RSA private key.That AES key was then used to decrypt the actual request body.The server-side implementation accepted requests with a validity window of around 30 seconds to prevent replay attacks. However, this still wasn’t enough to stop me.The 32-byte random array is stored across 8 stack slotse is encryption dataNow we need to simulate the encryption and decryption code (there’s no need to know the server-side private key). That means:If the unique code var n = t.toString(); appears in the response body, we log it as an encryption request.For decryption, if the unique code var n = r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(), t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8); appears in the response body, we print the server’s response.Below, you

Obfuscation Isn’t a Fix, And It Cost Them $2,500 — A Real-World Case Study

A while ago, I performed a penetration test on a major web application owned by one of my clients. During the assessment, I identified several critical vulnerabilities. Although these flaws weren’t easy to find — they required in-depth analysis and carefully crafted requests — they posed a serious risk to the platform’s integrity and user data.

Given the severity of the findings, I expected the development and management teams to prioritize proper remediation. But instead, they chose a different path.

Rather than fixing the underlying security issues, they decided to encrypt the entire body of each HTTP request— for example, encrypting login credentials or parameter values — in an attempt to prevent attackers from understanding or reproducing the vulnerabilities.

Their idea was to “hide” the vulnerabilities behind encrypted traffic, giving them six months to work on actual fixes. In theory, this would slow down any attacker trying to identify or exploit the issues.

I explained why this approach wouldn’t hold. Obscuring insecure functionality doesn’t make it secure — it just shifts the problem and adds complexity without eliminating the risk. I even challenged them: if I could still exploit the vulnerabilities despite the encrypted requests, they would pay me an additional $2,500.

Spoiler: they did.

Let’s walk through the scenario, why encryption is not a substitute for proper remediation, and what this taught both sides about the real cost of avoiding fixes.

The first request is a POST request, in which data is sent encrypted within the HashData parameter. However, after decryption, the data appears to be unreadable.

Upon inspecting the JavaScript bundle (main.xxxxxxx.chunk.js), I identified a function named HashData, which was responsible for encrypting request data. This function was used in two key places, but only one of them leveraged a request interceptor pattern, which allowed injection or modification of outgoing payloads before being sent.

In this case (Second Place), the developer has used an interceptor method for the request in order to apply modifications. We use a breakpoint to sniff and analyze it.

Despite the code being minified, I was able to use online tools to beautify it and analyze the logic.

The encryption process involved the following:

- A random 256-bit key was generated for each request using a function like random().

- The request body was encrypted using AES, with this random key as the encryption key.

- The random key itself was then encrypted using a static RSA public key and attached to the request.

- The encrypted data was finally Base64-encoded and stored or transmitted (sometimes via localStorage or directly in the request).

The AES encryption function is defined as follows:

function s(e, t) {

var n = t.toString();

return r.a.AES.encrypt(JSON.stringify(e), n).toString()

}- e is the input data that gets converted to JSON and then encrypted.

- t is the encryption key.

- The function returns the encrypted result as a string (i.e., the server response).

Here’s a simplified version of the AES encryption logic:

function encrypt(data, key) {

return CryptoJS.AES.encrypt(JSON.stringify(data), key.toString()).toString();

}The AES decryption function is defined as:

function u(e, t) {

if (void 0 !== e) {

var n = r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(), t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8);

return JSON.parse(JSON.parse(n).data)

}

}- e is the encrypted data.

- t is the encryption key.

- The decrypted result is parsed from JSON and returned as the original data.

Here’s a simplified version of the AES decryption logic:

function decrypt(encryptedData, key) {

const decrypted = CryptoJS.AES.decrypt(encryptedData.toString(), key).toString(CryptoJS.enc.Utf8);

return JSON.parse(JSON.parse(decrypted).data);

}This means that the payload encryption relied entirely on a client-generated key — which I could capture at runtime using browser breakpoints — and a public RSA key for wrapping that AES key.

On the server side, the process was reversed:

- The encrypted AES key was decrypted using the server’s RSA private key.

- That AES key was then used to decrypt the actual request body.

The server-side implementation accepted requests with a validity window of around 30 seconds to prevent replay attacks. However, this still wasn’t enough to stop me.

Now we need to simulate the encryption and decryption code (there’s no need to know the server-side private key). That means:

- If the unique code var n = t.toString(); appears in the response body, we log it as an encryption request.

- For decryption, if the unique code var n = r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(), t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8); appears in the response body, we print the server’s response.

Below, you can see the request body and the server’s response.

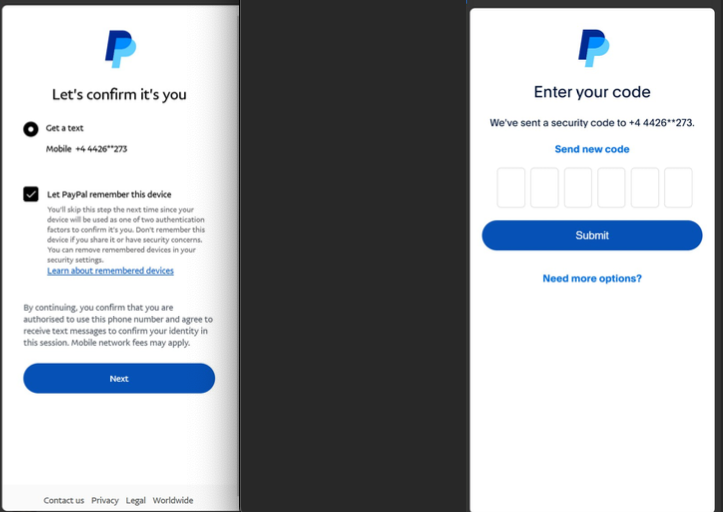

At the login stage, after entering the login credentials, another encrypted request is sent.

This HashData is Base64-encoded and can be decoded. Alternatively, if the response body contains the code var n = "", we print it.

This function encrypts the data and converts it to Base64. If needed, it also stores the result in localStorage. If t.isObj is true, the data (t.data) is first converted to JSON format and then encoded in UTF-8. The final result is then encoded in Base64.

How I Defeated It

I intercepted the browser’s request using a breakpoint on the unique call to HashData. Once the AES key and encrypted payload were available in memory, I simply logged them to the console.

From there, I could:

- Extract and replay encrypted payloads.

- Modify parameters (like credentials or object IDs) before encryption.

- Use the same AES encryption logic on my own custom payloads to interact with the backend.

- Decrypt server responses by breaking on the decryption routine that matched:

var n = r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(), t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8);

By simulating the encryption logic in my own scripts — without needing the server’s private key — I effectively reversed their encryption barrier and resumed exploitation:

For the Request Body:

var n=t.toString();

-> Replaced with:

var n=t.toString();console.warn(JSON.stringify(e));prompt("Request: " + JSON.stringify(e));

For the Secondary hash Request Body:

var n="";

-> Replaced with:

var n="";console.warn(JSON.stringify(t.data));prompt("Double Encrypted Body: " + JSON.stringify(t.data));

For the Response:

n=r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(),t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8);

-> Replaced with:

n=r.a.AES.decrypt(e.toString(),t).toString(r.a.enc.Utf8);console.warn(JSON.stringify(JSON.parse(JSON.parse(n).data)));prompt("Response: " + JSON.stringify(JSON.parse(JSON.parse(n).data)));

Conclusion

Two keys are used for encryption: a private RSA key and a public key that remains constant. For each request, a random 256-bit key is generated. The entire payload body is encrypted using this random key, and the random key itself is encrypted using the public key (a new random key is generated for every request). Each request is valid for 30 seconds.

On the server side, the data is first decrypted using the private RSA key to retrieve the original phrase. Then, the entire payload body is unencrypted using that original phrase.

As a result, the encryption algorithm implemented in the system can be bypassed, allowing visibility into both the request body and the server’s response. Therefore, it does not significantly contribute to the security of the system, especially when the system is already vulnerable.

This case reinforced a critical lesson in web security: Encryption is not a fix for broken logic. Obfuscating insecure functionality doesn’t make it secure; it only delays skilled attackers — and not for long. Any cryptographic control implemented on the client side can be reversed, debugged, or replayed.

In this case, I was able to exploit the exact same vulnerabilities as before, despite the encrypted traffic. Not only did this demonstrate the flaw in their strategy, but it also highlighted the importance of addressing the root cause, not just the symptoms.

Security through obscurity can buy time — but it’s a gamble. And in this case, the house lost.

Obfuscation Isn’t a Fix, And It Cost Them $2,500 — A Real-World Case Study was originally published in InfoSec Write-ups on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

What's Your Reaction?

![[Webinar] AI Is Already Inside Your SaaS Stack — Learn How to Prevent the Next Silent Breach](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiOWn65wd33dg2uO99NrtKbpYLfcepwOLidQDMls0HXKlA91k6HURluRA4WXgJRAZldEe1VReMQZyyYt1PgnoAn5JPpILsWlXIzmrBSs_TBoyPwO7hZrWouBg2-O3mdeoeSGY-l9_bsZB7vbpKjTSvG93zNytjxgTaMPqo9iq9Z5pGa05CJOs9uXpwHFT4/s1600/ai-cyber.jpg?#)